The Challenge Of Compliance: Landmark Court Verdicts Face Snubs, Defiance From Defendants

Winning a climate accountability lawsuit is one thing. Ensuring compliance with the court verdict is another matter.

When the European Court of Human Rights ruled in April this year that the Swiss government’s climate policies and protection measures were insufficient to safeguard citizens’ human rights, civil society statements and news headlines described the verdict as “historic” and a “landmark” decision or watershed moment. Court rulings in favor of young people in Montana who sued their state government in a rights-based climate case and a Dutch environmental organization seeking to hold Shell accountable for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in alignment with global climate goals garnered similar reactions.

But what happens when a state or corporation that loses a climate court case then seems to ignore the court’s decision or otherwise refuses to comply with the verdict? How impactful can these decisions – viewed as significant victories for climate litigants trying to hold governments or corporate polluters accountable – really be if they are challenged and ultimately not implemented or enforced? In both the Shell case (Milieudefensie v. Shell) and the Montana case (Held v. Montana), defendants are appealing the lower court rulings, and although those rulings remain binding during the appeal, plaintiffs in both cases say the defendants do not appear to be making genuine efforts to comply. The decision against Switzerland, meanwhile, has been met with backlash from the Swiss government. In an August 28 statement, the Swiss Federal Council criticized the European human right court’s ruling, with the Council saying it rejected “the right of association to lodge complaints to climate issues.” This comes after the Swiss Parliament in June voted to reject the ruling, a move that one international law expert warned sets a “dangerous precedent.”

“To declare that court judgments should not be complied with is a serious blow to the rule of law and a dangerous precedent,” Marco Sassòli, a professor of international law at the University of Geneva and commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists, said in a June statement responding to the vote by the Swiss Parliament’s lower chamber. That vote followed a June 5 vote from the Parliament’s upper chamber to adopt a declaration dismissing the human rights court’s decision as “judicial activism.”

The decision found Switzerland to be in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights (specifically, Articles 8 and 6) in a case brought by an association of elder Swiss women who argued they are disproportionately vulnerable to adverse health impacts from extreme heat that is worsening under global warming. The women contended their government was not doing enough to protect them, and while the Swiss domestic courts rejected their claims, the European Court of Human Rights took up the case and ultimately ruled in their favor. The ruling did not specify what actions the government should take, as that is a policy matter and not a legal determination.

Switzerland argues it is already doing enough to address the climate crisis, but its current climate policies and commitments are insufficient to be aligned with limiting warming to 1.5°C, according to Climate Action Tracker. The association of senior Swiss women that brought the lawsuit, KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz, called the Parliament’s declaration a “betrayal”, and these women along with Greenpeace Switzerland organized a petition with more than 22,000 signatories to push back.

The Swiss Federal Council, the executive branch body that is responsible for implementing court decisions, ultimately decided to align with the Parliament’s rebuff of the KlimaSeniorinnen case ruling. In a statement, the Council said that, like Parliament, “it is critical of the interpretation of the [European Convention on Human Rights] with regard to climate protection. It is also of the opinion that Switzerland meets the climate policy requirements of the ruling.” Greenpeace Switzerland and the Swiss climate seniors issued a scathing response, saying the Federal Council “attacks our human rights…By refusing to review and strengthen its climate protection policies in line with the human rights obligations detailed by the ECtHR, the Federal Council continues to aggravate ongoing human rights violations.”

The Swiss government’s move to reject the ruling is concerning and these types of snubs generally undermine the authority of courts, said Joana Setzer, a climate litigation expert and Associate Professorial Research Fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. “The Parliament’s statement refusing to implement the Court's ruling is a political statement that challenges the independence and legitimacy of the judiciary,” she told Climate in the Courts. “At the same time, unfortunately it is not unusual for countries to disregard rulings by the [European Court of Human Rights].” Setzer pointed to data from the European Implementation Network reporting that nearly half (49%) of the leading judgments issued by the Strasbourg-based court over the last ten years are still pending implementation as of January 2024.

There are enforcement mechanisms in place through the Council of Europe, the organization of European states that is subject to the European Convention on Human Rights. “We will probably first see political and diplomatic pressure from other member states of the Council of Europe against Switzerland’s position,” Setzer said. “The Council of Europe can also impose fines on countries that fail to implement [European Court of Human Rights] judgments.” Continued noncompliance could lead to further proceedings before the court, which “can ultimately lead to the state being expelled from the Convention system,” Setzer explained.

Shell Defying Dutch Court Order?

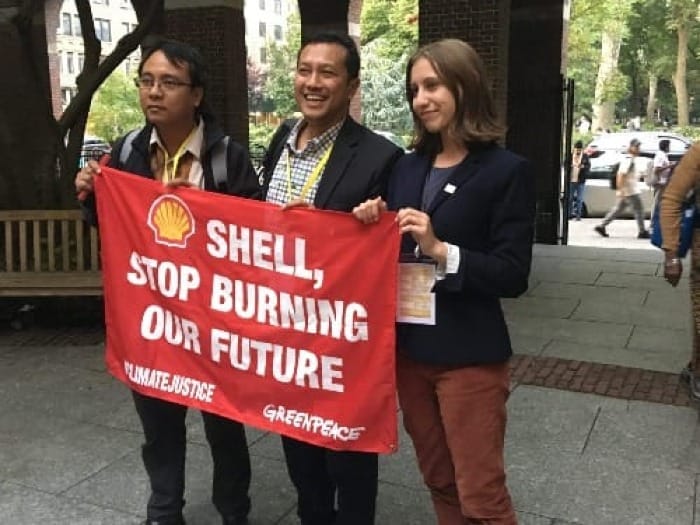

Most climate lawsuits filed to date have been brought against governments, but increasingly climate litigation is targeting corporate actors. One of the most high-profile of these cases saw the Dutch environmental organization Milieudefensie taking the oil and gas major Shell (formerly known as Royal Dutch Shell) to court in the Netherlands alleging the company was in breach of its obligations under Dutch and international law given that its business contributes significantly to global climate pollution. In May 2021, the District Court in the Hague delivered a groundbreaking judgment in favor of Milieudefensie, ordering Shell to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across its entire supply chain – including emissions that result from use of the company’s products (Scope 3 emissions) – by 45 percent by 2030. The ruling was hailed as major victory in the fight against climate change and the first time that a fossil fuel company was held liable for its role in fueling the crisis.

Shell promptly appealed the verdict, and the Dutch appeals court heard oral arguments earlier this year. In the meantime, climate campaigners have suggested that the company is not complying with the district court’s order, which remains binding.

Reports from Oil Change International and Milieudefensie reveal that Shell continues to expand its oil and gas operations since the 2021 court verdict. A 2022 analysis of Shell’s oil and gas assets, for example, found that the company authorized the development of ten new extraction projects since the court ruling and owns stakes in more than 700 assets yet to be developed. “The study has shown that, despite the climate case ruling, Shell is developing new oil and gas fields and is still drilling,” Milieudefensie’s Nine de Pater said, adding that the data suggests that “Shell has no intention of taking the judge's ruling seriously.” An updated analysis released in March 2024 revealed that Shell has now approved 20 new oil and gas projects since the verdict and has stakes in over 800 fields yet to be developed. Shell’s continued oil and gas expansion since the court ruling, according to Oil Change International and Milieudefensie, suggests the company is “defying orders to align its plans with what is required to curb the climate crisis.”

Shell refutes these suggestions and says it believes it is complying with the district court order. “As we wait for the outcome of the appeal, we are taking active steps to comply with the ruling,” the company states on its website. “We believe the actions we are taking to deliver our energy transition strategy are consistent with the court ruling and its end of 2030 timeline. This includes the investments we are making in low-carbon fuels, renewable power, and hydrogen; in addition to making changes to our upstream and refinery portfolios.”

However, Shell’s actual investments and business plans tell a different story. As Oil Change International’s “Big Oil Reality Check” report released in May 2024 points out, Shell has cut its capital investment in solar and wind energy by over 40 percent in 2023 compared to the previous year. The company has also reneged on a previous target to decline oil production by 1-2 percent annually to 2030 and plans to grow its liquefied natural gas (LNG) production and sales by up to 30 percent through 2030. Additionally, Shell earlier this year indicated it would reduce the emissions intensity of the energy it sells by 15 to 20 percent by 2030, a slight weakening of its previous pledge of 20 percent.

Shell may be counting on the district court ruling ordering the company to slash its emissions 45 percent by 2030 being overturned on appeal, but even if the Dutch appeals court upholds the ruling, Shell will likely seek review from the Dutch Supreme Court. That will take more time to resolve, meaning Shell could further delay implementing the district court order all while the 2030 deadline inches closer.

“One can expect that corporate defendants will seek a range of avenues to avoid being subject to judicial rulings that they disagree with,” said Michael Burger, executive director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School. He noted that Shell has not only appealed the district court ruling, but also relocated its headquarters from the Netherlands to London.

That doesn’t mean that Shell is off the hook, however. “The court ruling is provisionally enforceable, meaning Shell must comply even during the appeal process,” Setzer explained. “Failure to do so can result in penalties,” she said, “and continued non-compliance can exacerbate legal and financial pressures on the company.”

Setzer described some of the penalties and enforcement mechanisms that could come into play. “Courts can impose fines and sanctions on entities that fail to comply with rulings,” she said. “Entities that refuse to comply with court orders can also be held in contempt of court.” Furthermore, “governments and regulatory bodies may also be able to revoke or suspend licenses and permits required for the corporation’s operations. Continued non-compliance can also lead to additional lawsuits and legal actions. This can include new cases filed by affected parties or additional charges brought by regulatory bodies.”

“More broadly, ignoring court rulings can lead to a reputational damage. This can impact the corporation's market value, investor confidence, and customer loyalty,” Setzer said. “For multinational corporations, non-compliance can lead to international pressure and actions from foreign governments and international organizations.”

Montana Challenges Historic Ruling in Youth Climate Case

While a decision on Shell’s appeal of the 2021 verdict remains pending, another landmark court ruling in a US climate case is being challenged and awaits a final decision from a state Supreme Court. That ruling came in August 2023 in the youth climate lawsuit Held et al. v. State of Montana, the first case of its kind in the US to go to trial. The trial court judge Kathy Seeley ruled in favor of the youth plaintiffs, finding that the state government violated the Montana constitution’s guarantee of the right to a clean and healthful environment through a policy that prohibited consideration of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions during the fossil fuel permitting process. Seeley’s decision invalidated the policy, which the state’s Republican-controlled government enacted into law as an amendment to the Montana Environmental Policy Act (MEPA).

Montana promptly appealed, and the matter is pending before the Montana Supreme Court, which held a hearing on the appeal in July. The state argues that the policy at issue, which concerns MEPA, has no bearing on its substantive permitting decisions, and that the trial court “does not have the power to affirmatively order State agencies to analyze GHG emissions or climate change.”

But attorneys and experts supporting the youth plaintiffs say that the state could and should be analyzing climate impacts under MEPA in the wake of Seeley’s ruling, which remains in effect as the state’s attempt to have the ruling paused (request for a stay) was unsuccessful.

Anne Hedges, director of policy and legislative affairs at Montana Environmental Information Center who served as an expert witness for the Montana youth plaintiffs, told Climate in the Courts that following the August 2023 ruling, the state continued to issue fossil fuel permits without doing any climate analyses. Then earlier this year, the state’s Department of Environmental Quality started doing limited and “cursory” emissions evaluations that fail to disclose the vast majority of a project’s projected contribution to climate pollution. “What they are doing is they are feigning confusion,” Hedges said. “They are pretending like they don’t understand the [Seeley’s] decision, and that they are not mandated to do a climate analysis. And they are waiting for the Supreme Court to tell them that they’re wrong. So they are hedging their bets by performing perfunctory climate analyses that don’t provide any [real] information.”

Melissa Hornbein, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center and co-counsel for the youth plaintiffs, argued that the state’s response suggests that defendants are not complying with Seeley’s order. “Initial environmental analyses conducted in the wake of the Held decision essentially noted the decision but argued that because it was on appeal, the agency wouldn't be complying with it,” she told Climate in the Courts, adding: “DEQ has begun to include an extremely rudimentary emissions analysis that we do not believe complies with the Court's order in Held.”

Burger, however, said that Seeley’s order did not explicitly mandate that the state do comprehensive greenhouse gas emissions analyses and make its permitting decisions accordingly. “I think Montana is correct in reading that opinion as not directing the agency to make any substantive decisions one way or another with respect to permitting decisions,” he said. In this regard, is the young Montanans’ victory more symbolic with a favorable decision that will result in little substantive or practical change?

Burger’s answer to that is that court decisions like the one handed down by Seeley are not merely symbolic as they have real legal effect. “But,” he said, “the ability of the courts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is somewhat limited.”

The solutions to the climate crisis, ultimately, “are not going to be dictated by judges in courtrooms,” Burger said. “Courts are a critical part of addressing the climate crisis. But they’re not a silver bullet.”