Montana Kids Just Won Their Landmark Climate Lawsuit. Here's Why.

Article originally published by Drilled

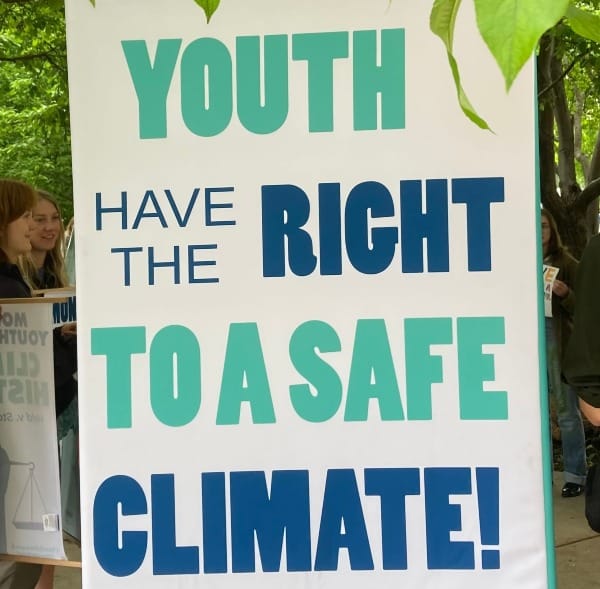

Sixteen young Montanans have accomplished something unprecedented in U.S. history – holding their government accountable for exacerbating the climate crisis and thereby violating their fundamental constitutional rights. In a ruling released August 14, 2023, district court judge Kathy Seeley agreed with the young people: they have a right granted by the state's constitution to a healthy environment, and that right is being violated by the state government's refusal to consider climate impacts in its permitting decisions.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but first it’s important to point out that courts outside the US have already ruled that governments are harming their citizens or violating human rights in their woefully inadequate responses to what climate scientists have warned is a full-scale climate emergency. From Colombia to Germany to the Netherlands, citizens and young people have taken their governments to court and won. But so far no climate accountability lawsuit in the US has seen similar success, including municipal and state lawsuits against fossil fuel majors as well as youth cases against governments. No case had yet even made it to trial, with the exception of New York’s securities fraud case against Exxon in 2018 (which Exxon ultimately won).

That is, until this June when the 16 youth plaintiffs – ranging in age from 5 to 22 - in the case Held v. State of Montana put their government on trial. It was the first-ever constitutional climate trial in this country, and first in a youth-led climate lawsuit. Similar cases, including one at the federal level, all spearheaded by the nonprofit law firm Our Children’s Trust, had for the most part been dismissed. The cases all argue that the government’s authorization of a fossil fuel-based energy system contributes to dangerous climate change and particularly harms our kids, depriving them of fundamental constitutional rights like the rights to life, liberty, and dignity. But Montana’s constitution expressly guarantees the right to a clean and healthful environment, and it extends this and other inalienable rights to the state’s youth. The Held case therefore charged Montana’s government with violating the constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment (among other fundamental rights), arguing that the state’s pro-fossil fuel permitting policies damage the climate and the environment.

The trial in the state capital of Helena started June 12 and ran for six and a half days. It attracted national and even international media attention. I was there in person the entire time covering it, observing from the jury box where members of the media were assembled. This trial was history in the making, as it was the first time that young people gave live testimony of their lived experiences with climate impacts, supported by detailed testimony from scientific experts explaining these impacts and the government’s role in worsening them. This testimony from youth plaintiffs and their expert witnesses took up the first week of trial.

By contrast, the state of Montana took just one day to deliver its defense. The state called only three witnesses - two high-level officials from one of the defendant agencies, and a free-market economist whose cross-examination lasted longer than his direct testimony. That was it. No scientific experts and no presentation of climate science.

In terms of the weight of evidence presented, the plaintiffs’ side appeared much more substantial. So then, what was the state’s defense? Examining the defendants’ claims and characterizations reveals just how weak it was and provides some basis for understanding how the young plaintiffs managed to win.

“It’s a MEPA trial”

The state’s defense ultimately seemed to center around a strategy of characterizing the case as narrowly as possible. Rather than engaging substantively on the climate issue at the heart of the case, state lawyers argued the trial was solely about a “boring” procedural statute – the Montana Environmental Policy Act (MEPA). This is the state equivalent of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that requires the government to conduct environmental reviews of proposed major actions or projects; it’s a bedrock environmental law that allows for public participation and transparency.

The Montana version of this law – MEPA – used to allow agencies to evaluate climate impacts in these reviews, like the federal law does. But in 2011 the state legislature amended the statute to prohibit consideration of impacts beyond state borders. This implicitly barred assessments of climate pollution, which is inherently transboundary in nature. The youth lawsuit against the state, filed in 2020, challenged this MEPA “climate change exception” provision, along with provisions in the state’s energy policy that specifically promote fossil fuels. Then the 2023 Montana legislature, in attempts to quash the lawsuit before trial, eliminated the energy policy statute and again amended MEPA to replace the 2011 version with one that explicitly bans consideration of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change in environmental reviews, both within and beyond state borders.

It is technically true then, that at the time of the trial, the legal challenge before the court was specifically the constitutionality of the MEPA ‘climate change exception’ provision, or what the judge called the ‘MEPA limitation.’ Just weeks before trial, the judge dismissed the other legal claim challenging the state’s pro-fossil fuel energy policy. But to look at the MEPA provision in a vacuum is to ignore critical context of the state’s preferential treatment of fossil fuel development. As one expert witness for the youth plaintiffs testified, Montana has never denied a permit to a fossil fuel project.

State defendants argued repeatedly that MEPA is strictly procedural, and therefore has no bearing on permitting decisions. “It’s a MEPA trial and that’s not where we permit,” Chris Dorrington, director of the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (one of the defendant agencies) said from the witness stand. But in a pre-trial order rejecting the state’s request for what’s called summary judgment – a ruling issued without a trial – Judge Kathy Seeley quoted the Montana Supreme Court: “[p]rocedural, of course, does not mean unimportant.”

The state’s characterization of the court proceeding as a “MEPA trial” and not a climate trial ignored the fact that the MEPA provision at issue was squarely about climate change. By prohibiting the consideration of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change in environmental reviews, Seeley ruled that provision is at odds with Montana’s constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. At issue here is not how MEPA works, but how the state’s dismissive treatment of climate change endangers the youth plaintiffs and degrades Montana’s environment.

“Not a scientist”

During the trial, the state apparently decided it would be best to ignore climate science altogether and to claim that Montana’s emissions simply do not matter on a global scale—a faulty strategy given that Keeley's ruling includes not one but two sections on climate science.

It is quite remarkable (and telling) that in a climate change trial, the state defendants failed to present any climate science during its defense. In an unexpected twist, they even decided at the last minute not to call their one scientific ‘expert’ – climate contrarian Judith Curry – to testify.

“We were expecting that this trial would involve a battle of the scientific experts,” Prof. Michael Gerrard, founder of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, told me. “But after they heard the testimony of the plaintiffs’ scientific experts, the State’s lawyers decided not to fire a single shot in this battle, and they withdrew the one scientist they had been planning to call. They apparently decided that this would be a losing fight.”

The state attorney's office did not respond to a request for comment.

The exchanges and testimony inside the courtroom revealed that state officials either have little understanding of climate change and climate science, or are deliberately choosing to ignore it in favor of other interests.

On day 2 of the trial, when Assistant Attorney General Thane Johnson cross-examined plaintiffs’ expert witness Cathy Whitlock, a climate scientist and professor emeritus at Montana State, he asked her to explain the climate modeling scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports – the two types of scenarios are known as Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). But during this line of questioning, he repeatedly misstated the acronyms. Johnson called the former scenario “RPC”, and then he referred to the “ICP” (meaning the IPCC), and he again got this acronym wrong in calling it the ICPP. At one point he said: “I’m going to write that down, there’s a lot of Cs and Ps involved.”

The following week, when youth plaintiffs’ counsel Melissa Hornbein of the Western Environmental Law Center cross-examined Sonja Nowakowski, head of the Air, Energy, and Mining Division at Montana DEQ, the agency witness refused to answer a pair of questions with a very obvious answer. Hornbein asked whether greenhouse gas emissions harm the ‘environmental life support system’ and whether they contribute to depletion or degradation of natural resources. Nowakowski responded with the classic deflection line: “I’m not a scientist.”

That line has been a go-to among climate denying Republican politicians. But in the state’s closing argument, Michael Russell, another assistant attorney general, claimed it would be inaccurate to place Montana’s Republican-controlled state government in the denial camp. “Plaintiffs have essentially characterized the state as so-called climate deniers,” Russell said, arguing that state defendants do acknowledge the scientific consensus on climate change and saying they agree that activities the state authorizes do result in greenhouse gas emissions.

And yet, the state recently enacted a law requiring agencies to ignore these emissions and their climate impacts during MEPA environmental reviews. In other words, state agencies are by law mandated to deny requests to evaluate a proposed project’s climate pollution. How is that anything other than climate denial?

“The state’s climate deniers want to make sure that their denial is embodied in a statute, and that the science doesn’t have any role to play in an environmental assessment,” said Phil Gregory, an attorney for the youth plaintiffs. Ultimately, the court agreed with his argument. In her ruling, Judge Seeley found that this MEPA's limitation on considering greenhouse gas emissions violates the Montana Constitution.

To the extent the state did address climate change during the trial, it argued that Montana’s greenhouse gas emissions don’t matter. “Montana’s emissions are simply too miniscule to make any difference,” Russell contended during his opening statement.

But as climate policy analyst Peter Erickson explained during his expert testimony on the plaintiffs’ side, Montana’s total annual CO2 emissions – 166 million tons (based on 2019 data) – are on par with annual emissions of entire countries like the Netherlands and Pakistan. “To call [Montana’s] emissions miniscule is then to call the emissions of over 100 countries of the world miniscule,” Erickson said. “Montana’s emissions matter”, he emphasized.

That’s especially true given the state authorizes quite a lot of fossil fuel extraction, especially coal. Erickson calculated that fossil fuel extraction in Montana results in approximately 70 million tons of CO2 emissions annually, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions from more than 14 million passenger vehicles on the road. Moreover, coal not yet extracted represents an enormous amount of CO2. Montana is said to have the largest recoverable coal reserves in the entire country.

Given that context, it seems a bit absurd for the state to claim that its emissions are “too minuscule” to matter. As Gerrard said: “The state's principal defense was that Montana plays too small a role in contributing to climate change for them to be required to do anything about it. This is despite the fact that Montana is the state with the largest coal reserves, including part of the Powder River Basin, which has been called the Saudi Arabia of coal.”

Furthermore, it is the scientific consensus that every ton of CO2 or GHG emitted adds to the climate problem. This is explicitly stated by the IPCC in its Sixth Assessment Report.

And in a court of law, such evidence and facts matter.

An “airing of political grievances”

In its closing argument, the state also tried to claim that this dispute ought to be a fight solely reserved for the legislature. In other words, courts have no business acting as a check on the legislative and executive branches, since the state’s power is derived from its people and people can directly choose their political representatives through elections.

That line of reasoning is just plain wrong. State legislatures do not have ultimate power, as the US Supreme Court recently confirmed in an important case on election authority. Contrary to Russell’s assertion that the plaintiffs’ case amounts to an “airing of political grievances that properly belongs in the legislature not a court of law,” the lawsuit is grounded in claims of alleged constitutional violations. Courts have a duty to assess the constitutionality of the political branches’ conduct and policies. That’s how a constitutional democracy works.

Moreover, many of the Montana plaintiffs are still too young to vote. In his closing statement, Russell suggested the plaintiffs could “legislate by ballot initiative and lobby their legislators” and continue “advocating their position in public to generate the political will necessary to enact their preferred policies into law.” The young Montanans are of course already engaging in climate activism, and yet, as one plaintiff said, state government officials “continue to promote fossil fuels.” Several other plaintiffs testified that they believe the state is “prioritizing profits over people.” And people are allowed to go to court when the state infringes on their fundamental rights.

As plaintiffs’ counsel Nate Bellinger, senior staff attorney at Our Children’s Trust, stated in his closing: “It’s worth remembering other times in our nation’s history when the political process didn’t work to protect people’s basic human rights. Segregation, women’s rights, equal and adequate public schooling, marriage—time and time again, the political will of powerful majorities was struck down by courts, based on the compelling evidence before them, courageously correcting the injustices thrust on the people. Today, the injustice squarely before this Court is the proven harms of these young people wrought by climate change caused by a fossil fuel-based energy system imposed and perpetuated through the law.”

What happens next?

The state will almost certainly appeal, and the case could end up before the Montana Supreme Court. So while the youth plaintiffs' win is historic, there is a chance the judgement will be overruled.

Regardless of the outcome, today the Montana plaintiffs have won. They succeeded in forcing their government to be put on trial. That is a huge deal because it allowed for science to form the basis of the evidence, and demonstrated that government policies are often at odds with science – especially when it comes to climate. The Montana plaintiffs also succeeded in getting their day, or in this case their week, in court to testify and let their voices be heard. And they succeeded in securing a historic ruling in their favor. It may inspire further youth climate activism including more youth-led climate litigation.

18-year-old plaintiff Lander Busse said he hopes the case will be “starting a trickle down of other litigation and activism nationally,” adding: “It feels like the beginning, really.”